Entries Tagged as 'Uncategorized'

Just saying

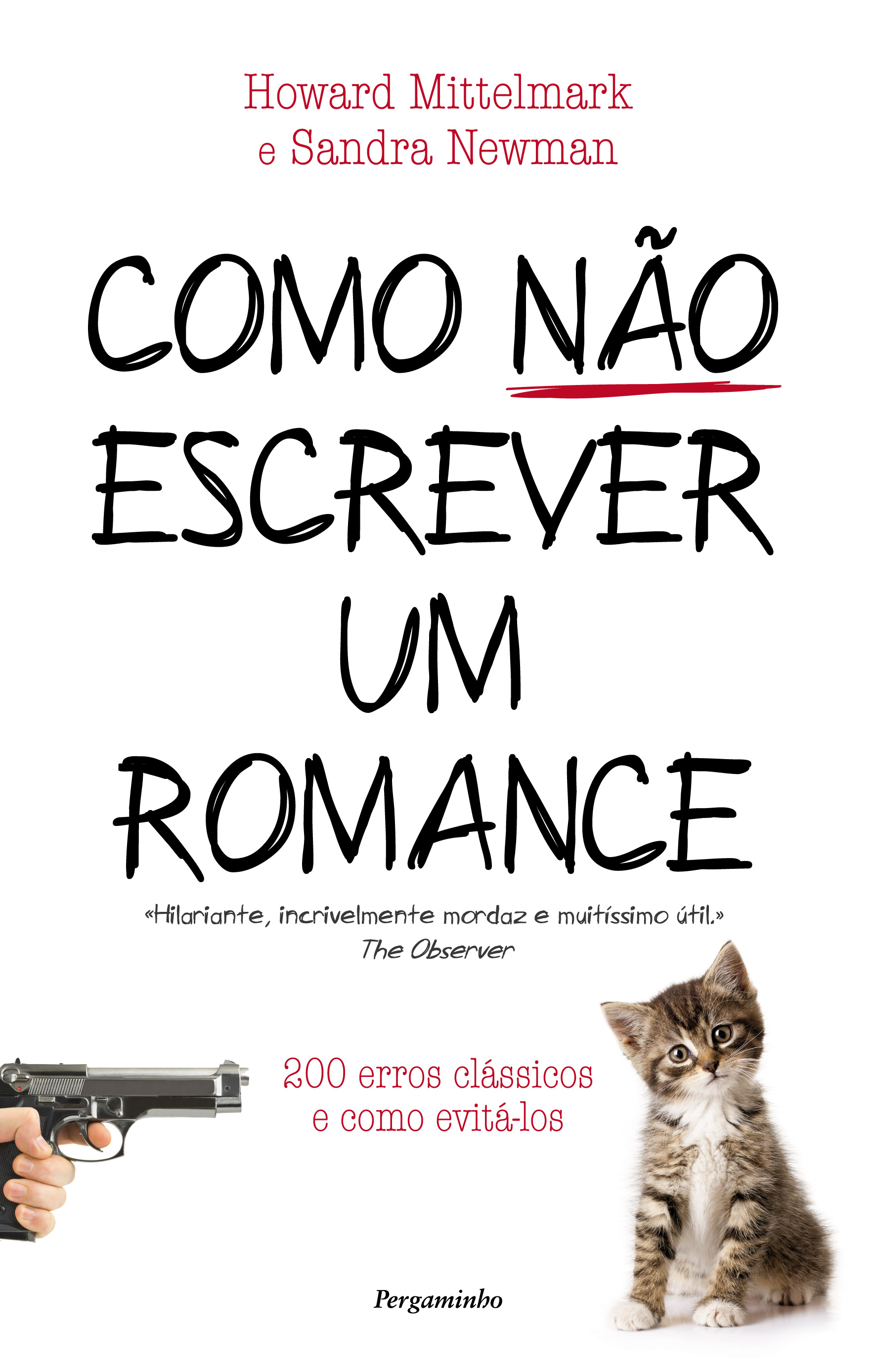

I read this book, twice, wrote a novel and now I’m a successful published novelist. This is the single most useful book on how to write a novel ever written, ever, by anyone in the entire universe, and you dismiss it to your cost.

–Ben Aaronovitch, bestselling author of the Rivers of London series

Jean-Robert, the Genre Bear

GRRrrr, boys and girls! I’m Jean-Robert, the Genre Bear!

Right now, your body is going through lots of scary changes, so Howard and Sandy asked me to have a talk with you about literary genres.

As you grow taller and different parts of your body start to take on startling and unexpected dimensions, you’ll also find yourself thinking about what genre you would like to write in. You’ll hear things in the street about genres, and the best thing to remember is that all of it is true. But before you start making any big decisions, let me tell you some things that will help you as you learn to move your body in ways that will upset older people.

Today I’m going to talk about “romance.” More books are written about people falling in love than about anything else. In English, these books are called romance novels. But in most Romance languages, any kind of novel is called a romance, not just romance novels. Romance languages are called Romance languages because they come from the language that people used to speak in Rome, before Rome was invaded by the Goths. Although the languages that come from the language of Rome are called Romance languages, the language of Rome was called Latin, and some romance novels have characters called “Latin lovers,” who usually speak Spanish.

The Goths learned to write after invading the Roman Empire, but they did not write Gothic novels. Gothic novels were a type of novel written during the Romantic period, which followed the neoclassical period, which was influenced by the Roman Empire, which is why styles of the neoclassical period are called Empire. Another style of the neoclassical period is the Regency style, and novels set during this period are called Regency romances. Regency romances never have sex in them.

Other romance novels have sex in them, and they are still called romance novels, unless there is a lot of sex, and then it is called erotica. If it has even more sex in it, and less romance, it is called pornography, unless it is literary fiction, in which case it is just called fiction. Literary fiction is a genre of fiction which is not genre fiction. All the literary fiction that was ever written is called Western literature, and the first Western literature was written by a man named Homer, who was blind. Western literature does not include westerns, which are a genre of fiction set in the American West, and always have cowboys and sometimes have Indians. Americans write westerns, and lately a lot of Indians write novels. Novels written by Indians are always literature.

So, remember, boys and girls, it’s perfectly natural to want to experiment with genres, and it probably won’t make you go blind, or at least not for a very, very long time.

Sandy’s New Book

is out today in the US, from Gotham Books (April for the UK edition from Penguin).

The Western Lit Survival Kit is smart and funny, sweet and savory, smooth and chewy, an entertaining romp through the Western canon with a sly and savvy guide. Here’s the first review, from Kirkus:

A clever tour d’horizon of what you might encounter in a Great Books course in college.

At first glance, Newman’s (Read This Next, 2010, etc.) work comes across as a comedy routine meant to poke many of the received-opinion greats in the eye with a sharp stick, much in the manner of Ovid, one of the author’s favorites. And that is certainly part, but far from all, of the truth. First, a typical zinger: “As a general note, all of Homer’s heroes were illiterates who considered rape and genocide normal. Generations of European boys were raised on Homer. Just saying.” The author is not here to venerate—though Shakespeare gets a pretty deep genuflection—or eviscerate: She appreciates genius and fine, intellectually thrilling writing. With each writer, she gets to the nub of a work or style from the outset (“The Bronte home was a little biosphere of literary misery”), and she is not afraid to venture her true feelings: Of Tristram Shandy: “Page for page, it’s possibly the funniest novel ever.” Newman is a serious fan of humor and a good roll in the hay: e.g., Sappho, Tom Jones and Gargantua and Pantagruel. Montaigne’s Essays also get the nod, as do Dickinson, Kafka, Eliot and a holy host of others. Half the fun here is quibbling with her choices and tinkering with her rating system: How important are the books considered? How accessible are they? How much fun? Newman assigns each a number from 1 to 10, and despite all the levity, she has clearly (if seemingly surreptitiously) read deeply and brought serious rumination to the proceedings.

A sly piece of work—though you still should read the books.

You can get it from the Store At The End of the Universe or the scrappy underdog.

How Not To Write A Novel Goes To College II

If you’re teaching How Not To Write A Novel in a writing course, let us know. We like to keep tabs on these things. To show our appreciation, you’ll be entered in a drawing to win a copy of the new Teacher’s Edition of How Not To Write A Novel, which offers you the full and unchanged text of the original book, but with a richer, more mature subtext.

(Read about the original How Not To Write A Novel Goes To College here, in this HNTWAN ClassicPost.)

Do You Need How Not To Write A Novel?

We don’t want you to waste your time with a book that’s not right for you. We want every copy of How Not To Write A Novel to reach only those people who need it most.

To that end, we have designed this simple quiz so that you can find out if your life might be improved by our book.

What about I, the literary novelist?

It has oft been said, and we will say it again, oft; our book is not for everyone. Yes, it is for men and women of all genders, creeds, and sleep numbers. It is for the hot and the not, the tomato and the tom-ah-to, the hokey and the pokey. Whatever your favorite color, there is a home for you at How Not to Write a Novel.

Still, some have come to us and said “How Not to Write a Novel is not for me, for I have an MFA: I have achieved mastery of fine arts. I have wrestled fine arts to the ground, and they have cried like a little girl. I–I–am their master! What use do I, the literary novelist, have for How Not To Write A Novel?”

Nonetheless, we as people and writarians, are for everyone, even if our book is not. (It can be bought by anyone, though, here. A CRAZY bargain!!) It has oft been said that Howard and Sandy are the kind of people whom you either love or hate. How true that is, except for the love part. But those who hate us need our help far, far, more than those who love us, in a hypothetical situation where someone loved us. Those who hate us should seek our help without wasting a second on thought. We know what the nay-sayers will say. They will say nay. But you are a grownup now with a college degree and you can put your fingers in your ears and go “la la la!” until they stop.

Now that you have your MFA, you may think it’s too late for you to write a dreadful novel. Howard! you are thinking, Sandy! How will I ever be able to write the bad novel of my bad dreams??? Quell those fears! Experience teaches us that years of study and training are no obstacle to unreadable, inarticulate prose. For you we have written How Not To Write a Novel II: How Not To Write A Novel Goes to College. The title, not the book. For us to truly exhaust this topic would take months, hundreds of pages, and a substantial advance. But just off the top of our heads, we can offer some tips and techniques to overcome all your time and effort.

Watch this next

Our new book, Read This Next, is out in the US tomorrow, so we thought we’d bring you the video our friend Marianne Petit made for us.

Secrets of Writing

“One of the reasons why a lot of my characters are high is that it’s easier to write for people who are stoned, who are not very smart and don’t know big words.”

–Judd Apatow